CNN

—

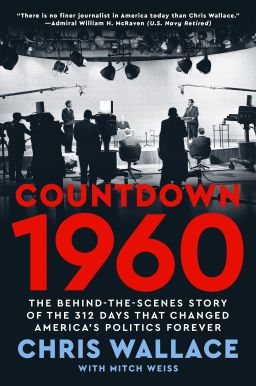

Editor’s Note: This essay is adapted from Chris Wallace’s book, “Countdown 1960.”

The 1960 presidential election changed everything. It was the first to feature televised debates between the two major-party candidates. It was the first in which both candidates were born in the 20th century. And as is true in the current presidential campaign, the 1960 candidates were both fascinating characters.

John F. Kennedy – the scion of a rich, powerful family – ran the first truly modern campaign. Traveling the country in the “Caroline” – the private plane his father bought him– Kennedy used sophisticated polling and television to address voters’ concerns. His campaign took full advantage of Kennedy’s good looks and keen intellect.

Richard M. Nixon lacked Kennedy’s glamor. But the sitting vice president had a big advantage in real-world experience – even confronting Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev face-to-face in the famous Moscow “kitchen debate.” And he had served eight years under the hugely popular President Dwight D. Eisenhower during a period of peace and prosperity.

But while the 1960 campaign is a great political story, full of drama and improbable plot twists, that was not the driving force that led me to write my new book “Countdown 1960: The behind-the-scenes story of the 312 days that changed America’s politics forever.” No, the reason I wrote “Countdown” is because of its relevance to the 2020 election – and to the continuing debate right now about our electoral process.

To put it simply: There is good reason to believe the presidential election of 1960 was stolen. And yet, in 1960, the candidate who “lost” refused to contest the results and interfere with the peaceful transfer of power. What happened back in 1960 turns current talk of voter fraud, rigged elections and the refusal to accept the final results on its head.

To understand the contrast, take a look at what happened on Election Day, November 8, 1960. The polling margins in at least seven key swing states were gone. Kennedy seemed to have a slight lead, but the race was breaking late for Nixon. The final difference in the popular vote was 112,827 – a margin of just 0.17%.

But it’s what happened in several key states that made the difference. Kennedy won Illinois and its 27 electoral votes by just 8,858 votes out of more than 4.7 million cast. But Kennedy had a big advantage: the support of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and the Cook County Democratic machine. As the results came in on election night, the vote totals from Republican areas in downstate Illinois were reported first. The count from Chicago and Cook County was surprisingly slow. But when Daley’s precincts reported, Democrats rolled up “fantastic pluralities” for Kennedy, according to The Chicago Tribune from November 1960.

A single neighborhood in Chicago’s Ward 4 reported 25,770 votes for Kennedy, while Nixon got 7,120. In Ward 24, Kennedy collected some 24,000 votes to Nixon’s just over 2,130. But those lopsided margins were the least of it. In Ward 2, Precinct 50, almost 80 votes were cast – even though the precinct had only 22 registered voters. And when Republican election officials tried to investigate suspicious activity, they discovered ballot boxes were either empty or missing.

The activity in Texas was even more egregious. In the home state of Kennedy’s running mate, Sen. Lyndon Baines Johnson, the Democratic ticket won its 24 electoral votes by 46,266 votes out of more than 2.3 million cast. But just consider the more than one million paper ballots. Texas had created an almost impossibly confusing system. Voters using those ballots not only had to mark their choice for president, but also had to scratch out the names of all the other candidates they weren’t voting for.

Understandably, thousands of voters failed to follow instructions. It was then up to precinct judges to decide whether ballots that were not fully marked should be counted – or disqualified. Those election judges were overwhelmingly Democrats. In Republican-leaning precincts, investigators found up to 40% of Nixon votes were disqualified. But in Democratic-dominated areas such as Starr County on the Mexican border, almost none of the ballots were thrown out.

With all the evidence of irregularities, Nixon came under considerable pressure to contest the election. Kentucky Sen. Thruston Morton, the Republican Party national chairman, refused to concede defeat and was joined by other top GOP officials. Some historians believe that behind the scenes, Nixon encouraged them to challenge the results in Illinois and Texas and other key states.

But publicly, the vice president was a good loser. At 12:45 p.m. on November 9, when it was clear that Kennedy was the winner, Nixon sent him a telegram, saying, “I know you will have the united support of all Americans.”

On November 14, Nixon was in Key Biscayne, Florida, recovering from an exhausting and unsuccessful campaign. Kennedy suggested a meeting in the interests of national unity. Nixon agreed, and after spending an hour with the president-elect, told reporters he viewed their getting together as an example of how democracy works, adding that it was all about the peaceful transition of power.

For someone who lived through the events of 1960 (I was 13), that is why what happened in 2020 was so deeply shocking. I spent my life knowing the rules of democracy in America. Somebody won, somebody lost, both sides acknowledged it, and we moved on. That’s just the way it was.

But 2020 shattered that. And I’m not sure we will ever return to the same unspoken confidence that our political leaders will accept the rules and abide by them.

I will never forget the moment it all changed. Around 2:30 a.m. on November 4, 2020 – in the middle of election night – with the race still far too close to call and millions of votes still to be counted, then-President Donald Trump appeared before a crowd of supporters in the East Room of the White House. Fox News, where I then worked, had projected that Joe Biden would carry Arizona, the first state either party had won in 2016 to be put in the other party’s column in 2020.

“This is a fraud on the American people. This is an embarrassment to our country,” Trump declared. “We were getting ready to win this election. Frankly, we did win the election.”

It wasn’t a fraud, but everything to come all flowed from there. The dozens of lawsuits; the call to Georgia’s secretary of state to “find” votes; the effort to put together slates of false electors in states Trump lost.

If there is one moment that crystallizes the differences between the 1960 and 2020 elections, it was on January 6, the day set by the Electoral Count Act of 1887 for Congress to meet in a joint session to tally the electoral votes of each state and for the vice president to certify the winners of the election.

On January 6, 2021, Trump summoned a crowd of tens of thousands of angry supporters to a rally at the Ellipse. “We will never give up. We will never concede,” he told them. And he gave the crowd their marching orders: “And we fight. We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

Trump had been pressuring his vice president, Mike Pence, for days to reject the electoral votes for Biden and overturn the election. When Pence announced he was not permitted to do that under the Constitution, the mob stormed the Capitol, and even set up gallows outside while chanting, “Hang Mike Pence.”

Contrast that to the events of another January 6, in 1961 – a remarkable day that saw Nixon presiding over the counting of the electoral votes. Standing on the House rostrum after the count was complete, the voices of members of his party pushing him to contest the election surely ringing in his ears, Nixon still noted the moment’s core truth: This was the “first time in 100 years that a candidate for the presidency announced the results of an election in which he was defeated, and announced the victory of his opponent.”

Nixon declared that Kennedy, who was in the House chamber, had been elected president. And he added, “I don’t think we can have a more striking and eloquent example of the stability of our constitutional system and of the proud tradition of the American people of developing and respecting institutions of self-government.”

That is why I wrote “Countdown 1960,” and why I think it has such relevance today. Sixty-four years ago, with the most powerful position in the world at stake, and with the difference between victory and defeat on a razor’s edge, Nixon chose to do the right thing– what was best not for himself, but for his country.

As we have learned so painfully, that choice is no longer guaranteed.