CNN

—

Isabel Zelaya was beginning his shift at a beef slaughterhouse in rural Tennessee on a spring day in 2018 when agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement burst into the processing area and, with guns drawn, ordered him and others to toss their tools to the ground.

Zelaya, who was in his 60s at the time of the raid, explained that he had legal status to live and work in the US, but agents nonetheless zip-tied his hands and led him into a van, according to court records.

He and about 100 other Latino workers were shuttled to a nearby National Guard Armory for processing.

The operation, at the time the largest workplace immigration raid in at least a decade, sent a signal that then-President Donald Trump’s tough talk on illegal immigration would be matched by hard-nosed action.

The move triggered a swift response by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a civil-rights nonprofit with a long history of using the legal system to defend vulnerable groups.

Days after the raid, the Alabama-based organization dispatched a team of lawyers to the small towns where the workers lived and were being detained.

The attorneys from SPLC and the National Immigration Law Center would spark a flurry of legal activity that included a successful wage-theft complaint against the meatpacking plant and a precedent-setting class-action suit – with Zelaya as the named plaintiff – that led to a nearly $1.2 million settlement with the feds for racial profiling and excessive force. It was thought to be the first class action settlement against the US government tied to a workplace immigration raid, experts said.

Now, with Trump back in the White House after having promised during the campaign to unleash “the largest deportation operation in American history,” the cadre of attorneys at SPLC who amounted to a first line of legal defense for undocumented immigrants is no more.

This past summer, in a move that inflamed already raw tensions at the storied civil rights institution, the SPLC laid off all 35 staffers – 23 of them lawyers of various specialties – in its Immigrant Justice Project, former employees said. (SPLC confirmed that the program was terminated but declined to provide specific figures.) That immigration division, in the words of the organization, took on “cases that few private lawyers will accept, seeking systemic reforms and representing victims of injustice.” The layoff was part of a larger restructuring effort at the well-funded organization.

A CNN review of the work of SPLC’s immigration program found that it played a key role in holding ICE, privately run detention centers, and employers of undocumented immigrants accountable, particularly in the southeast region, which is home to some of the nation’s largest and most troubled detention facilities.

SPLC’s now-disbanded Immigrant Justice Project also had a large subsidiary unit – called the Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative (known internally as “SIFI”) – that provided free legal representation to undocumented immigrants held in detention. That unit of immigration attorneys enabled hundreds of detainees to be released on bond while their immigration or asylum cases were tried, thereby enhancing their chances of success, former employees and SPLC officials told CNN.

Above all, immigration advocates say, the attorneys had a watchdog effect on a system of confinement that can be walled off from public view.

“SPLC is an immensely resourced group,” said Lisa Graybill, who used to work at SPLC and is now vice president of litigation and legal strategy at the National Immigration Law Center. “The loss of those resources and that partnership is really significant.”

SPLC officials insist they fully intend to continue serving the immigrant community. They characterize the cuts as a reorganization that will replace a case-by-case approach with a big-picture strategy that addresses abuses at the systemic level.

“We plan on focusing on broad, systemic issues that have maximum impact for immigrant communities,” Derwyn Bunton, the SPLC’s chief legal officer, told CNN. “We organized our resources into larger, issue-focused legal teams. And this strengthens our ability to help bring challenges to unjust immigration policies and practices across our entire practice at the local, state and federal levels.”

Asked whether SPLC plans to hire new attorneys to beef up its roster, Bunton was non-committal.

As it stands now, the organization has no immigration attorneys, though Bunton said it has attorneys with immigration experience and will not shrink from combating the Trump administration’s plans for mass deportations.

“As the threat has scaled up, so have our efforts to pursue litigation against them by shifting to more broadly challenging unfair and discriminatory legislation and policies,” he said.

Bunton declined to share specifics on immigration suits or initiatives in the works, saying they are in the “investigation phase.”

SPLC leaves large void in immigration advocacy

This past summer, SPLC shed 78 jobs, or about a fifth of its staff, in its restructuring efforts. While the round of layoffs touched multiple departments, none were wiped out as thoroughly as the Immigrant Justice Project.

The mass layoff reverberated throughout the nation’s network of immigration-focused nonprofits.

Michael Lukens, the executive director at the Amica Center for Immigrant Rights based in Washington, DC, said the size of the void left by SPLC’s dismantled program can’t be overstated – particularly in southeastern states like Georgia and Louisiana.

“The thought of having some of the largest detention centers in the country with nobody outside of a few local nonprofits doing the work that SPLC was doing is really troubling,” said Lukens, whose organization provides some individualized representation for detainees in Georgia but whose main focus is on Maryland, DC and Virginia.

Meanwhile, Lukens added, the second Trump administration’s immigration policies and rhetoric are even more hardline than the first.

“It’s a lot crueler this time,” he said. “And it’s also a lot more xenophobic and outwardly hateful.”

SPLC’s pullback coincides with a sense of public exhaustion on the left that stands in contrast to the full-throated opposition to Trump’s election in 2016. That fatigue has taken tangible form in donation dollars, which, by some accounts, haven’t exactly flooded the coffers of nonprofit civil-rights groups in the same way they did in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s first win.

“There was a massive mobilization of people during Trump 1.0 and it seems like that’s slowly picking up steam, but I do think people are somewhat tired,” Lukens said. “It’s hard to get everybody as motivated as they were the last time.”

Publicly available tax documents show that SPLC, like other nonprofits, witnessed a surge of donations around the time of Trump’s first election. In 2017, the group launched the “SIFI” unit that provided pro-bono legal services to detainees in Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi; it included about nine immigration attorneys, former employees said.

All of them were laid off in June.

10 deaths since 2017

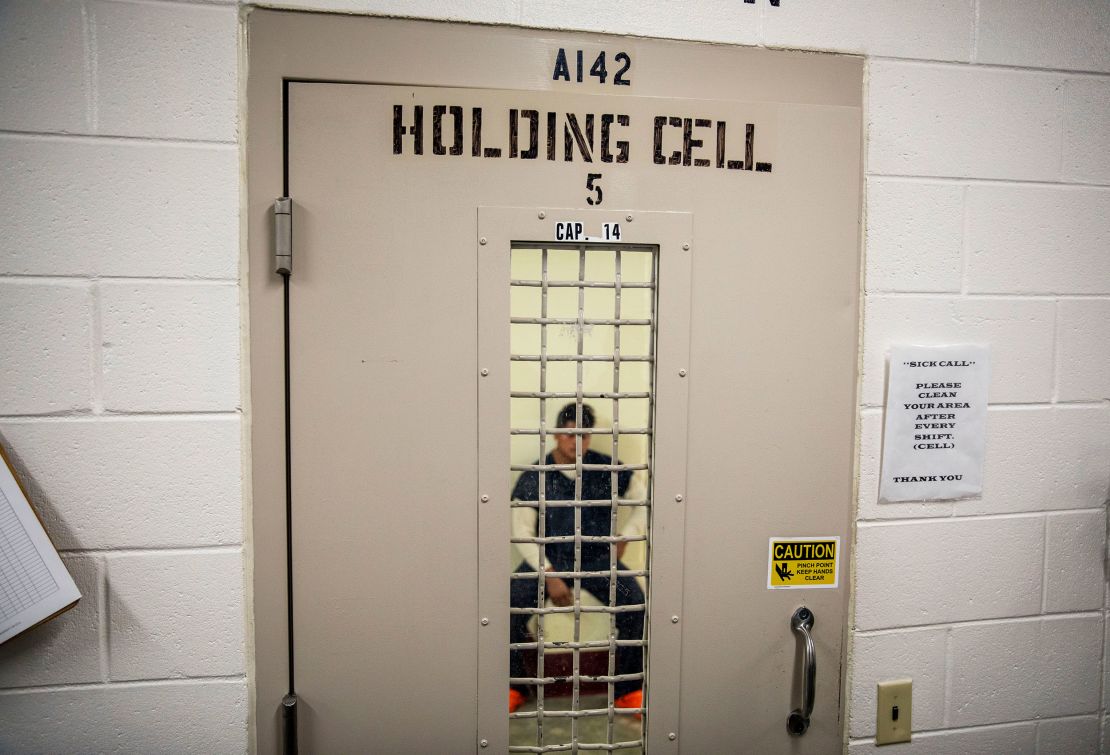

Among the immigrant lockups served by the SPLC attorneys was the Stewart Detention Center, a remote facility in Lumpkin, Georgia, that has gained notoriety for its harsh conditions. It has seen 10 deaths since 2017, the highest in the nation, according to a June ACLU report.

Immigration advocates say in addition to providing legal aid, SPLC’s attorneys had a daily presence in the Stewart facility that was itself a safeguard against abuses and unsafe conditions, which have allegedly included significant mold growth, food-poisoning due to spoilage, medical neglect and excessive use of solitary confinement, according to a December report by El Refugio, a nonprofit that provides assistance to detainees at Stewart.

A spokesperson for CoreCivic, the private company that runs Stewart, disputed the claims in the report, saying the facility is audited regularly without notice.

“Facility conditions at (Stewart) are evaluated and inspected on a weekly basis, including sanitation practices, HVAC and plumbing systems, food service equipment, and overall security,” the spokesperson said in an email. He added that the food service at Stewart recently earned a perfect rating from the state.

Stewart is currently the third-largest detention facility by population of the 90-plus across the country, according to a research group from Syracuse University.

By providing legal aid to detainees at that and other complexes, the SPLC attorneys filled a gap in the immigration system, which, unlike the criminal justice system, does not guarantee legal representation. This means the vast majority of undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers go without it. (Unlike prison inmates, detainees in immigration detention centers can typically be released if they agree to return to their home countries.)

Across the country, detainees are given a list provided by the Justice Department of organizations that provide pro-bono legal assistance; at Stewart in Georgia, the SPLC’s group was often the only one on it, immigrant advocates say. The American Bar Association does offer services, but they are generally educational.

“I honestly don’t have any other numbers to give them right now,” said Amilcar Valencia, the executive director at El Refugio, which provides lodging at a house near the Stewart facility for people visiting detainees. He said he worries the situation at Stewart is about to become “chaotic.”

“It’s just going to be a lot for the loved ones to just even locate their family members, let alone trying to find legal support,” Valencia said.

Former SPLC employees say in 2023 they were able to help nearly 100 detainees from Stewart get released early on bond; the facility typically holds about 1,875 ICE detainees.

SPLC officials have indicated that this is too much effort for too little payoff. Margaret Huang, the CEO of SPLC, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution this past summer that the individualized approach was like to “trying to empty the ocean with the teaspoon.”

By focusing more on class-action cases, Bunton of SPLC said the organization can help immigrants beyond the confines of what happens in the immigration courts.

“With immigrant communities it’s going to be what happens in the streets in their towns throughout the South; it’s going to be what happens to their families, to housing, to all these sorts of things,” he told CNN.

But attorneys who were laid off insist that meeting with individual detainees at the detention centers sometimes led to bigger cases or produced valuable intel for them.

“You can’t just show up somewhere and gain everyone’s trust and have them tell you these really difficult stories that could put themselves at risk without having built those relationships for a long time and gained trust and promise to stay with them,” said Erin Argueta, the lead SPLC immigration attorney at Stewart until she was laid off; she now works for another immigration-oriented nonprofit.

Layoffs exacerbate internal turmoil at SPLC

Internal tensions at SPLC have been brewing since at least 2019, when staff turmoil led to the ouster of its co-founder, Morris Dees, now 88.

The organization fired Dees after he was investigated twice for “inappropriate conduct” and 20 employees sent a letter to executives claiming that the SPLC’s moral authority had been compromised by allegations of “mistreatment, sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and racism.”

Dees, who denied wrongdoing, had enjoyed a celebrated career that included a lawsuit in the 1980s against a large and violent Ku Klux Klan outfit that left the white supremacist group bankrupt. Reached by phone, Dees declined to comment for this story.

SPLC’s effort to unionize was born amid the 2019 staff revolt against Dees, said Rachel Janik, a union officer at SPLC.

“It brought the people together who would become our organizing committee,” she told CNN.

SPLC officials say the organizing effort had nothing to do with who it decided to let go last summer.

But Janik said the layoffs “really struck at the heart of our union.”

“They laid off our unit chair,” she said, adding that more than 60 union members were terminated. “Multiple officers were laid off. A ton of stewards were laid off.”

Both sides, however, agree that the layoffs had little to do with finances.

Indeed, the Southern Poverty Law Center remains a fundraising powerhouse. Its total revenue in 2023 – nearly $170 million, most of it from contributions but much of it also from investments – surpassed the prior year’s intake by about $30 million, according to its latest publicly available tax filings. The organization’s ever-growing store of total assets that year came to nearly $750 million.

As part of its reorg, SPLC has identified five key areas of focus for litigation moving forward: economic justice; voting rights; democracy, education and youth; inclusion and anti-extremism; and decarceration and decriminalization.

Immigration matters, SPLC officials said, could fall under any of those pillars.

But advocates worry that the lack of boots on the ground at detention centers in the southeast will have harsh effects for many individuals who – like many of the slaughterhouse employees in Tennessee – get swept up in the raids.

“They will not be able to find an attorney to help them,” Lukens said. “They won’t be able to seek bond. They won’t be able to really fight their case.”

Tania Wolf, who was laid off from her SPLC position in Louisiana as a senior project coordinator in the immigration program, was more blunt.

“It’s going to lead to increased amounts of suffering for people in detention,” she said.