More than a decade ago, it seemed the tide might turn against pervasive campus sexual violence. In a 2011 letter, under President Obama, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights charged universities with taking effective steps to end sexual violence, a form of sex discrimination that is prohibited by Title IX.

For the next few years, the issue of campus sexual violence gained attention from the U.S. government. In March 2013, Obama signed into law the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act which, among other provisions, required many universities to offer campus-wide sexual violence prevention programming. Over the last decade, four-year colleges have instituted prevention programs that educate students on consent in relation to sexual violence. In 2022, President Biden reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act and called for the development of the Interagency Task Force on Sexual Violence in Education, which Congress charged with providing recommendations to educational institutions for best practices in sexual violence prevention.

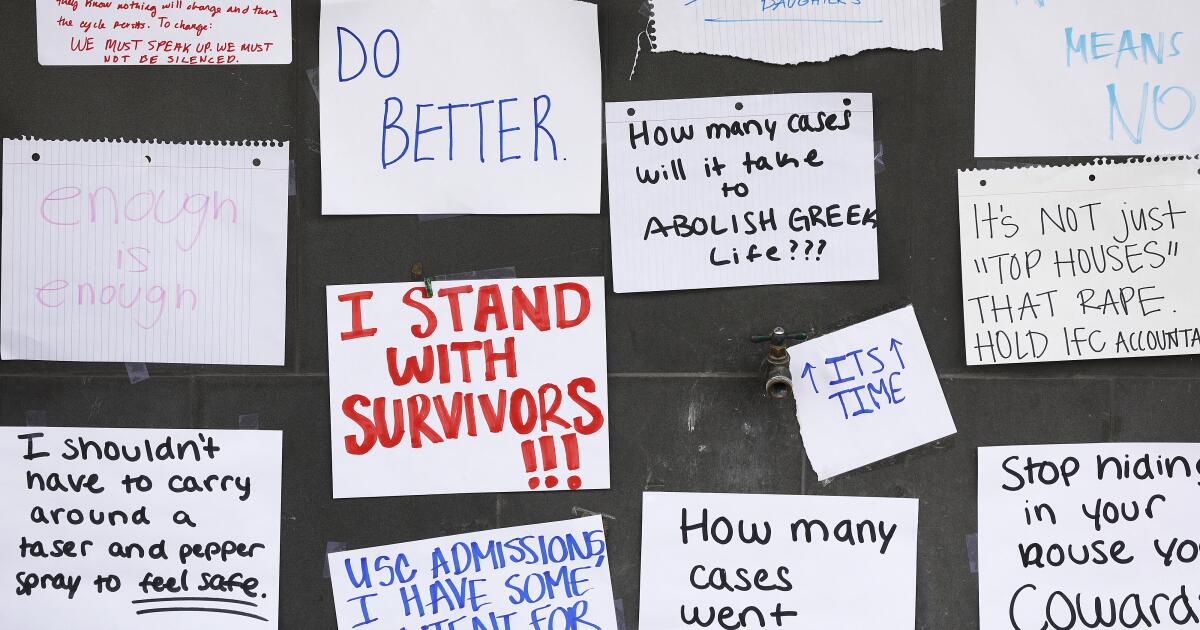

Yet this increased governmental guidance and heightened institutional efforts have not achieved much concrete progress. “The conversation has grown fiercer, but not necessarily more productive,” Sara Lipka, an editor at the Chronicle of Higher Education, wrote. Although debate persists around the oft-repeated statistic that 1 in 5 women experience nonconsensual sexual contact in college, it has not been convincingly debunked. Research suggests the risk of sexual assault is often higher for students with multiple marginalized identities.

Efforts to prevent sexual violence often fail because they follow a one-size-fits-all approach. Typical prevention programs focus on the significance of gender and ignore the significance of race. As a result, they often fail to support students who are women of color.

Take alcohol use, for example. Because it is one of the most studied risk factors for experiencing sexual violence in college, institutional prevention programs put a hyper-focus on the connection between alcohol and sexual violence. But this focus is not as useful for many women of color, who, studies suggest, drink less frequently than white students and experience less alcohol-related violence on campus. The decision to drink less is related to racial identity — some students, for example, abstain from alcohol to avoid hostile encounters with campus police.

There is also an intense focus on Greek life as a risk factor, given that sorority membership has been linked to a higher risk for experiencing sexual violence. Yet due to the racist history of traditional campus Greek life, many women of color continue to be excluded from membership in Panhellenic sororities, which are predominantly white.

Concerned about the exclusion of their perspective from prevention programs, I interviewed women of color survivors and asked them directly: What did they see as a primary risk factor for experiencing campus sexual violence?

Their answer is instructive for everyone: a lack of comprehensive sexual health education.

Almost all the women I spoke with encountered abstinence-only sex education before college. As one interviewee stated, the sex education she received taught her, “Just don’t do it. That’s the best thing.” This education, or lack thereof, influenced women’s vulnerability to sexual violence. Years of research show that an abstinence-only curriculum doesn’t work — it doesn’t reduce the amount of sex young people have or affect their contraceptive use. Instead, it often promotes a culture of fear, shame and silence around sexual health and fails to prepare students to recognize and engage in healthy adult relationships. It also reinforces discrimination and victim blaming.

Alternatively, an approach that teaches students not strict abstinence but comprehensive sexual health may act as a protective factor against campus sexual violence. One study at Columbia University found that female students who received pre-college sex education that included training on how to say no to sex — also known as refusal skills — were less likely to experience penetrative assault in college than students who did not receive this training. This more in-depth education would help all students, including young men, better understand consent and respect their own and others’ boundaries.

The lack of education on refusal skills, or most other aspects of sexual health, that I encountered in my research was, unfortunately, not surprising: Only 30 states and the District of Columbia require public schools to teach sex education. Seventeen states teach abstinence-only education, and more than half of states require schools to emphasize abstinence. The future for sex education does not look bright: The first Trump administration promoted abstinence-only education, a push that may return with a second Trump term.

And higher education doesn’t always close the gap. One woman I interviewed recalled how her college’s required prevention training lasted 10 minutes and focused only on consent. Another survivor told me that the prevention education video her school required her to watch featured “all these frat people. … All of [the actors in the video] were white. All of them were heterosexual. And [they] spoke in a way that assumed everyone was just like them.” The material was not relevant to her.

The lessons I drew from speaking with women of color survivors can benefit all students and institutions: A more effective way to prevent sexual violence is to teach young people early about safe and healthy sex and to account for identity in this comprehensive education.

Jessica C. Harris is an associate professor of higher education and organizational change at UCLA and the author of “Hear Our Stories: Campus Sexual Violence, Intersectionality, and How to Build a Better University,” from which this piece is adapted.